Understanding the Guitar’s Standard Tuning (E A D G B E)

The guitar’s standard tuning—E A D G B E—is so ingrained in our musical culture that it’s easy to overlook its deeper significance. Many guitarists learn it as a sequence of notes without fully grasping why this particular arrangement is used. But when you take a deeper dive into music theory, it turns out that this tuning is far from arbitrary. It’s designed to follow the natural geometry of music, making the guitar both intuitive to play and capable of generating a wide range of harmonic possibilities.

1. The Chromatic Scale and the Basis of Tuning

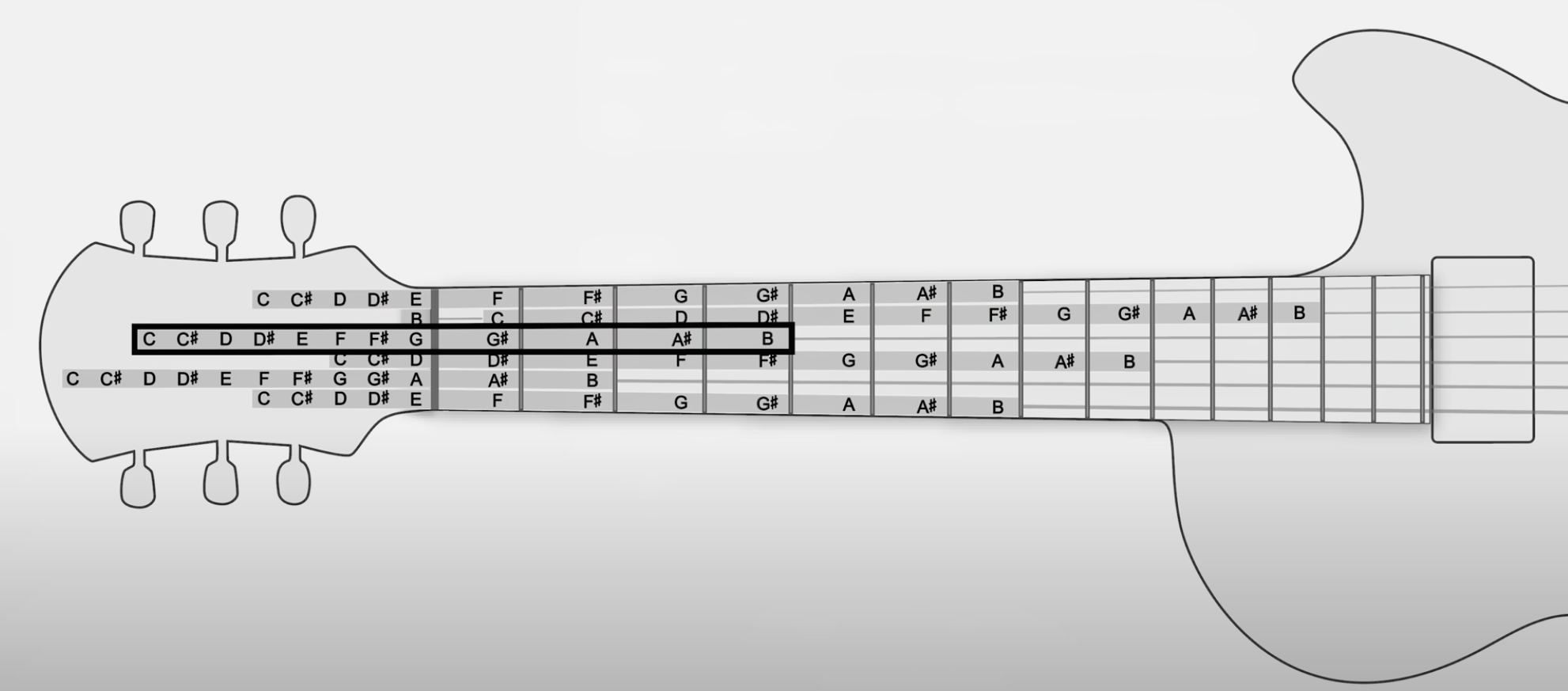

At the core of this tuning is the chromatic scale, which consists of 12 notes: C, C#, D, D#, E, F, F#, G, G#, A, A#, B. The chromatic scale is the foundation of Western music, and the notes in this scale are spaced one semitone (one fret) apart.

On the guitar, these 12 notes are arranged across the fretboard in a staggered manner. Each string plays a note in this scale, and the intervals between the open strings (E, A, D, G, B, E) are based on the relationships between these chromatic notes.

This arrangement may seem random at first, but it follows a logical structure rooted in music theory. The relationship between the strings is based on the circle of fifths, a harmonic sequence in music that organizes notes in a way that makes them sound naturally compatible. The arrangement of notes in standard tuning—E A D G B E—reflects a powerful harmonic structure that serves as the basis for most of the guitar’s capabilities.

2. The Circle of Fifths and Its Role in Tuning

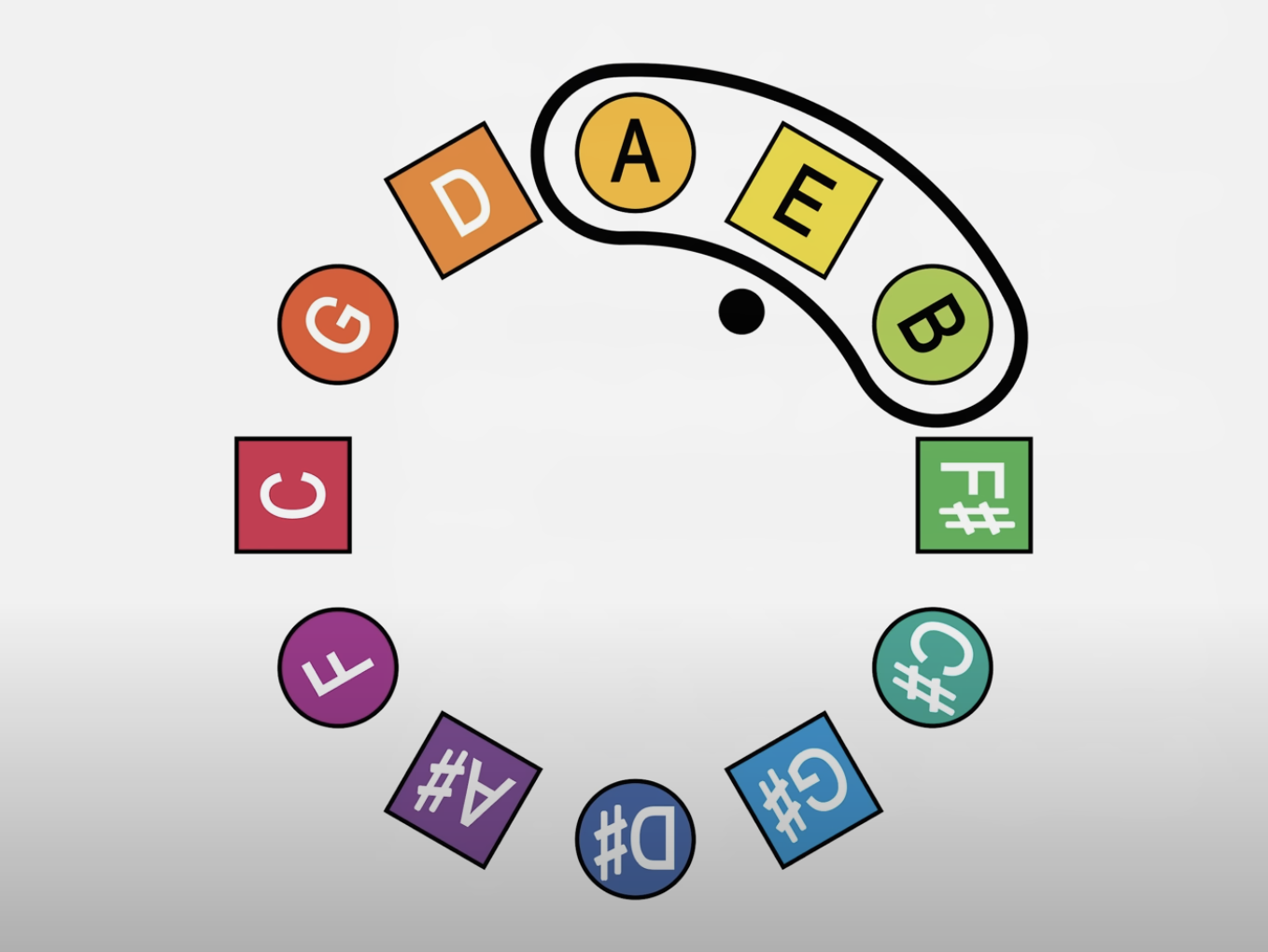

One of the most important patterns in music theory is the circle of fifths. The circle of fifths arranges all twelve notes of the chromatic scale in a circular formation, with each note being a fifth apart from its neighbor.

If we apply the circle of fifths to guitar tuning, we can see how the open strings’ notes (E, A, D, G, B, and E) are interconnected harmonically. For example look in the image :

- E is flanked by A and B, its closest harmonic neighbors.

- A is surrounded by E and D.

- D is nestled between A and G, and so on.

When you trace the path through the notes E, A, D, G, B, and E on the chromatic scale, an interesting shape emerges—a pentagram, or star. This symbol is significant because the notes E, A, D, G, and B form a pentatonic scale, a scale that is widely used in Western music due to its harmonious sound.

3. A Mind-Blowing Hidden Structure

Here’s where things get even more fascinating: the arrangement of the guitar strings, based on the chromatic scale and the circle of fifths, forms a contiguous block of harmonic relationships, which can be visualized using a color wheel analogy. Each string, when combined with the others, forms a coherent system, where the intervals between the notes create a seamless transition across the fretboard.

This natural progression, which connects notes in harmonic relationships, makes it easier for guitarists to understand and play scales, chords, and progressions. By understanding this, you can more easily navigate the fretboard, seeing how different shapes and patterns fit together.

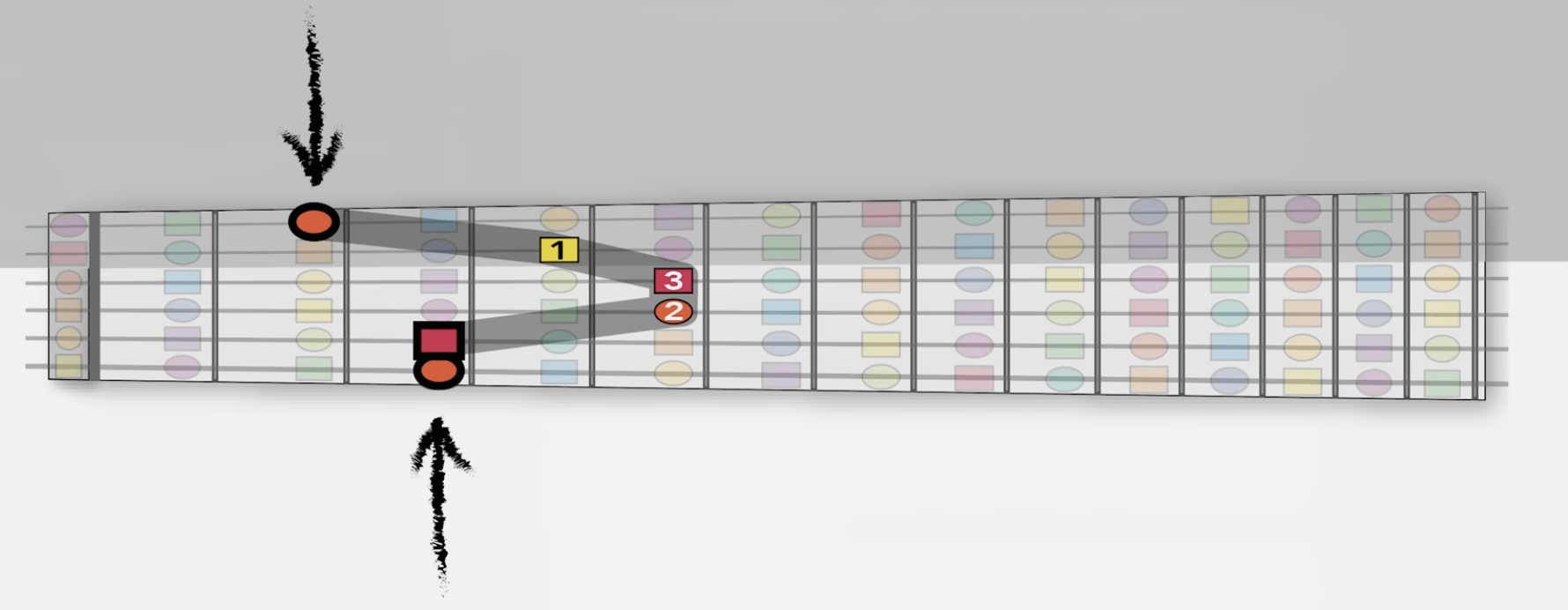

However, there is a slight shift in this pattern that occurs between the G and B strings. While most of the notes follow the circle of fifths and maintain a consistent spacing, the G string (being slightly out of alignment with the pattern) is shifted up a fret in relation to the B string.

This is not a mistake or flaw in the design—it’s actually a feature that allows the guitar to be more ergonomic and easier to play. Without this shift, the notes on the top strings (B and high E) would be too far apart for your fingers to form comfortable chords. This small shift allows the strings to be closer together, making it possible for the human hand to play the instrument with ease.

4. Why This ‘Kink’ at the Top Two Strings Is Actually Brilliant

The shift between the G and B strings creates what is known as a ‘kink’ in the otherwise consistent pattern. You might think this is a flaw in the guitar’s tuning, but it’s actually a clever adjustment that makes the guitar easier to play. This shift allows for more comfortable finger positioning when playing chords. For instance, basic chord shapes like the C major chord can be played more easily because the notes are physically closer together, allowing your fingers to reach them without overstretching.

Without this adjustment, the distances between notes on the fretboard would be too wide in certain places, especially at higher frets, making it nearly impossible to form simple chords. By shifting the top two strings, the guitar’s design becomes more ergonomic, accommodating the natural movement of the human hand.

5. The Practical Implications: What This Means for Guitarists

What this all boils down to is that the standard tuning is not some random sequence of notes. It’s a beautifully-designed arrangement that is based on fundamental music theory and perfectly aligned with the natural geometry of music. The staggering of notes across the fretboard forms an intuitive structure that helps guitarists visualize and play music more effectively.

In essence, the guitar’s tuning (E A D G B E) is designed to make the instrument both harmonically rich and physically playable. It allows for a vast range of musical possibilities, from basic chord progressions to complex scales and modes, all while keeping the instrument easy to navigate.

Conclusion

The guitar’s standard tuning isn’t something you need to memorize with a goofy mnemonic like “Every Apple Does Go Bad Eventually.” It’s a natural and purposeful design rooted in the geometry of music itself. By understanding the theory behind the tuning and recognizing the harmonic relationships between the strings, you gain a much clearer understanding of how the guitar works as an instrument.

References

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OcOBdVJ8eWY

Information

- date: 2024.12.11

- time: 01:15